You Dont Know the Way Comrade

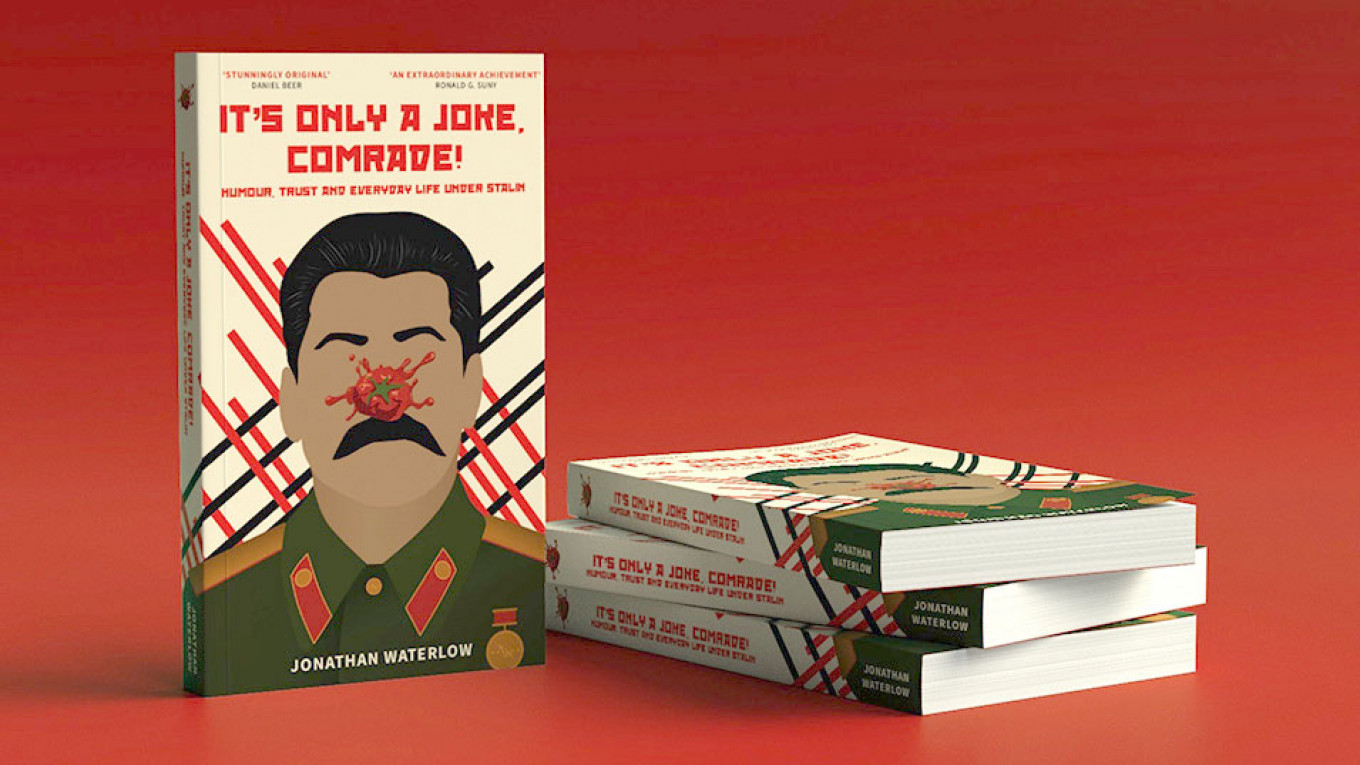

An exploration of political jokes told under Stalin, "It'south Simply a Joke, Comrade!" by Jonathan Waterlow, is possibly the funniest book to grow out of a doctoral project. Although it includes plenty of Soviet jokes and anekdoty (funny stories), "It's not a joke book!" Waterlow insists. Instead, the volume analyzes jokes in their historical context to consider accounts of public stance under Stalin. Drawing on 273 criminal cases of Soviet joke tellers, Waterlow introduces the concept of "crosshatching" to testify that political jokes were less a form of resistance than a style of sharing hardship, cultivating trust, and ultimately acquiescing to life under the regime.

The Moscow Times' Anna Kasradze spoke with Jonathan over Skype about his volume.

Q: How did you lot become interested in researching Soviet jokes of the Stalin era?

A: Since high school, I've been fascinated by Soviet history of the 1930s, but a lot of the historiography didn't brand sense to me. At that place were all the same scholars proverb that people must either take lived in perpetual fear and trauma or been completely brainwashed to purchase into the system. Nowhere in the earth is a population 100% for or against its government.

History books treated jokes as creative seasoning before returning to mass arrests and brainwashing. I wanted to employ jokes to understand how people tried to make sense of their lives. Most books on pop stance of that flow reflect the support/resistance separate, only jokes are much more cryptic. People are wrestling with complexities: "This is something unchangeable, only I'm finding a way to cope and deal with it." That doesn't brand y'all an absolute insubordinate or someone who hated the regime. Information technology helps you cope and move forward. Yous're able to hold conflicting ideas in your mind. Jokes are a more than fun, more interesting style to become into that, and they hadn't been examined for what they were worth. I think Wittgenstein said y'all could write a whole philosophy of the human condition using simply jokes.

Q: Where exercise y'all see this support/resistance binary today?

A: In the pop consciousness, at that place's just an paradigm of the gulag and repression and suffering. The Orwellian-Solzhenitsyn view dominates. At that place's not much sense that people lived rich lives—that also had a lot of pain and trauma—and found meaning. Jokes are an important way to discover meaning when yous don't control your circumstances. They assistance you experience that you have critical ability and can weave together a earth that makes sense to you. In scholarship, the resistance trope hangs in the background as an implicit supposition, similar the Stalin cult I mention in the book.

It doesn't undermine the seriousness and suffering of the purges to explore the other experiences people had at the aforementioned fourth dimension. People all the same went on summer walks in Gorky Park or had drinks and shot the cakewalk with friends while mass arrests were happening. Information technology'south not just more than realistic, it'south besides more respectful to empathise the richness of their lives.

Q: Practice y'all still find the jokes funny?

A: I exercise, but the problem is that jokes are super contextual. Lacking context, the authorities saw jokes as attacks instead of a style of letting off steam or sharing hardship. Frequently in talks virtually the book, I find myself maxim, "Hither are x things yous demand to know before this is funny."

Q: Did jokes reduce pressure on the regime to make incremental changes that materially improved people's lives?

A: I think you're right from an outside analytical signal of view, just the government saw jokes exclusively as acrimony and resistance. We oftentimes call back of jokes as a mode to stand up up against a dictator, but really sharing them helps the states get to work the next twenty-four hour period and get on with life. A lot of people accept emotional connections to anekdoty as resistance civilisation (maybe their families were involved), and they don't want to hear that jokes helped people to cope. I sympathize and respect that. People at the time could often feel like jokes said "No, I don't stand up for this," only the things that we do and say can feel like something only have a dissimilar result. I don't think there are any regimes that collapsed because people told jokes. Too oftentimes in history it'southward the people non telling jokes who bound on the barricades.

Q: What most surprised you during your research?

A: Finding these sources was surprising, because I was bodacious I was going to neglect. Some other surprise was that the government itself changed its view of humour over time. First, they considered information technology a dubious leftover of the pre-revolutionary past that needed to be corrected, but from 1935 they thought of it every bit a contagious mind virus and began censoring jokes fifty-fifty in the courtroom and court records. That'southward a whole new level of paranoia, which really doesn't imply a great deal of trust in their own credo or their ain people. Some other surprising thing was that nearly people who were telling jokes idea they were the exception, that other people weren't telling jokes in their shut circles of friends.

Q: What practise we not know about jokes under Stalin?

A: Nosotros don't know who the denouncers were, although it would potentially disclose fascinating stories about the personal circumstances behind denunciation. The criminal records don't make it clear who triggered the investigation or what sort of prior bad blood existed between these people. There's besides then much nosotros don't know about private people's stories: what joke-tellers were doing when things began to fall apart and how they got in problem.

Q: What are some of your favorite jokes?

A: I relish the really uncomplicated ones where people accept political party slogans and say "Thank you, Comrade Stalin!" or "Life has become more joyous!" when they get bad news. That just feels so existent then homo to me.

Q: What is the large take-away you hope readers get from the book?

A: The volume is an invitation not to treat people in the by so differently than nosotros treat ourselves. People come to complex and contradictory explanations of their lives as nosotros do. Jokes help us find a mode to acquiescence that feels better than anger or despair, but they don't make us rebels.

Q: What are y'all working on now?

A: I accept a podcast called Voices in the Nighttime where nosotros explore the human being condition ('learning how to human' equally we put it). I also have my own website, and I'm more than happy to be in touch with readers who accept questions or things they'd like to share about jokes, Stalinism, etc.

From Chapter 1: Kirov'south Carnival, Stalin's Cult

Saturation

At that place is no doubt that many Soviet citizens venerated Stalin, just in political sense of humour we can hear many others sharing critical opinions well-nigh him and his Cult on a twenty-four hours-to-solar day ground that rapidly presents u.s. with a very different, more complex image. Let's consider twoanekdoty which turned upwardly numerous times in the archival sources:

Stalin summoned a number of economists and told them he wanted to agree a feast for all the people, a feast and so nifty they would revel (пировать) for weeks. He asked the economists how much this would cost, just no 1 could say. Then one spoke upwardly and said it could be done very cheaply: 'Buy a unmarried bullet and shoot yourself – and then anybody will celebrate'.

Stalin was out swimming, but he began to drown. A kolkhoznik who was passing by jumped in and saved him. Stalin started to enquire the kolkhoznik what he would like as a advantage when the latter realised who he had saved. 'Nothing!' he said, 'Simply please don't tell anyone I saved you'.

In each anekdot, the underlying supposition is that the population at big hates Stalin and would prefer him dead. There'southward a sense hither that Stalin is the principal cause of people's suffering; as another anekdot had it, rather elliptically, 'In our country nosotros have such an artist that when he performs, the whole nation weeps'. More than straight, a Harvard Project respondent recalled a unproblematic pun, altering Stalin's propagated role as Leader and Teacher (vozhd' i uchitel') to Leader and Torturer (vozhd' i muchitel'). If Stalin was ultimately to blame for their hardships, then citizens could readily imagine that his decease would improve their lives.

As this implies, far from being a taboo subject field for mockery, or deemed to sit benignly above politics, Stalin was considered and treated in sense of humor as Public Enemy Number Ane: he was the default object of popular sarcasm, mockery and criticism, and was targeted more often than whatever other leading figure. As a afterwards Romanaian joke described their own dictator's, Ceauşescu'due south, cult, 'In laughter every bit in life, he is at the center'.

In fact, the very saturation of the Stalin Cult became a subject of mockery in its own correct. A letter sent to Andrei Zhdanov (Kirov'south successor every bit Petrograd Political party boss) makes this point in subtly absurdist style, detailing in a long list the ubiquity of Stalin'southward name by the later 1930s:

Honey comrade Zhdanov!

Exercise you not think that comrade Stalin'south proper name has begun to exist very much abused? For example:

Stalin's people'due south commissar

Stalin's falcon

Stalin's pupil

Stalin's culvert

Stalin's road

Stalin'due south pole [sic]

Stalin's harvest

Stalin'due south stint

Stalin's five-year plan

Stalin'south construction

Stalin'southward block of communists and non-party members

Stalin'southward Komsomol (it's already beingness called this)

I could give a hundred other examples, fifty-fifty of little significant. Everything is Stalin, Stalin, Stalin.

Although this writer went on to encode his message every bit constructive communication to the leadership, actually warning them of the risk of absurdity such a prevalence of Stalin's proper name engendered, many others seized on this absurdity direct. For example, a lawyer recalled that, in his workplace in Odesa, on the sign for the toilets someone appended the words 'named later Stalin' (туалет им. Сталина). Less overtly, some Komsomol members in Bashkirskaia oblast' amused themselves past renaming their canteen's slow cabbage goop 'Stalin soup' – an appellation that could sit down quite happily alongside the others on the list sent to Zhdanov.

This vein of sarcasm as a response to the overbearing nature of the Cult is neatly summed upward in an anekdot which recounts how, for an anniversary commemoration of Tchaikovsky's piece of work, there was 'a two-hour speech about Comrade Stalin and nothing said at all nigh Tchaikovsky'. A similar joke described how the centenary of Pushkin's death (1837) would be marked with the erection of a statue which, via several planning revisions, becomes a colossal statue of Stalin holding a pocket-size book of Pushkin'south poesy.

More significantly, rather than just mocking the Cult's excesses, by inverting the practice of associating Stalin with every chemical element of life or official policy, he could easily exist blamed for everything. When the abolitionism of student grants was announced in October 1940, Chiliad.V. Pen'kov blamed Stalin direct, yelling a parody of an official slogan back at the radio announcement in a room of his contemporaries: 'Thank you, Comrade Stalin, for [this] happy life!' Similarly, in Saratov, an unnamed girl was sentenced to five years for being late to work, to which she responded with withering sarcasm, 'Thank you, Comrade Stalin, for a happy childhood', mocking another famous slogan. And, in mid-1940 when the working twenty-four hours was increased from seven to eight hours, Lashina, an accountant in the Northwest shipping armada, ranted angrily to her colleagues, terminal, in tones of withering scorn, 'Thank you, Comrade Stalin, for stretching out your paw to us, although we take already stretched out our legs,' melding a propagandistic image of Stalin the paternal instructor with a colloquialism meaning 'to kick the saucepan'. She was not the but one to respond this way: 5.A. Marandzheev, the chief of staff at a musical instrument manufacturing plant, interjected during a radio broadcast of a lullaby praising Stalin, maintaining the high register of the vocal for comic issue, 'Hallowed be thy name, Stalin. The workers offered unto Stalin the cede of their half dozen- and 7-hr working days'.

How tin these anekdoty and biting one-liners fit with the generally accepted ideas about the Stalin Cult and its importance? Was its influence over people'southward understanding of and engagements with the regime much less than has so long been claimed? In fact, that Stalin was so often the chief target of mockery doesn't hateful that his Cult of Personality was unimportant or unreal. On the contrary, that he so ofttimes featured in disquisitional humour actually demonstrates how closely he was associated with the regime in the minds of the people. But beingness the symbol and center of both the Party and the Soviet Union wasn't always a good thing to be when criticism and discontent demanded a ready target.

What it does suggest, however, is that although (as countless historians have argued) the Cult'south significance grew disproportionately over the grade of the 1930s, many citizens responded to it much as they did to any other official land policy. That is, they received and judged it selectively and critically; information technology was neither embraced wholesale, nor was it simply dismissed out of hand. Responses depended on changing events, specific policies, and personal experiences. It is in any case rather unrealistic for us to expect to notice a static or even a singular stance of Stalin, even in the mind of a item private; people are simply too complex and contradictory for that. Yet when we ask questions most 'popular stance' we ordinarily want to find a nice, articulate answer rather than a mixed one, which is precisely what makes a continuing accent on the explanatory ability of the Stalin Cult so appealing. Only the Stalin Cult cannot simply 'explain' pop opinion to us, even if contemporaries frequently and pointedly used it to assistance explicate their difficult lives to themselves.

Annotation: For ease of reading, the footnotes have been removed from this department.

Excerpted from "It'south Only a Joke, Comrade." Copyright © 2018 by Jonathon Waterlow. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

fergusonsauty1960.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2019/08/03/its-only-a-joke-comrade-a66683

0 Response to "You Dont Know the Way Comrade"

Post a Comment